My trip to Japan in May started in Tokyo and went to the northernmost part of the island, to Aomori and Hirosaki. Over the three weeks of the trip we visited a number of museums that showcased textiles, along with temples and gardens. I’ve already described the hands-on workshops we took during the course of the tour, so now I’d like to focus on the wonderful textiles I saw in museums.

On the first day of our visit we combined seeing the Tokyo National Museum with the Imperial Palace, which are on the same grounds. None of the original castle from the Edo period remains. In fact, where that castle stood is now a traditional Japanese garden, which I enjoyed very much. There was a tale I didn’t fully comprehend about one of the shoguns from the Edo period deciding to have the river re-routed in order to have better views and stronger protection. I struggle to imagine how a river could be re-routed in a time long before modern equipment. Sorry I don’t have the details of this incredible feat. I did try to search online. Hey! If the Egyptians could do it, I’m sure the Japanese could as well.

Of course we all loved the rose gardens with views of Tokyo just beyond the grounds of the Imperial Gardens.

It was the museum that captured our imaginations. The second floor was devoted to textiles.

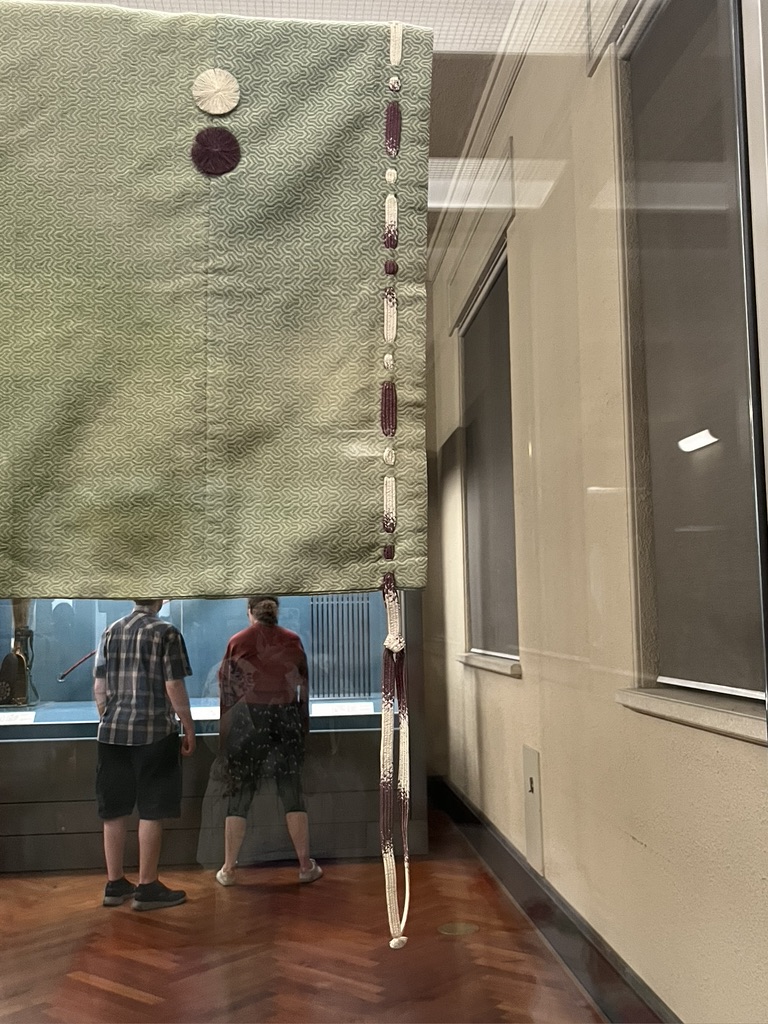

There was plenty of samurai armor on view, and I’m drawn to these wherever I find them. All the cream colored bits (and there is a lot of it, isn’t there?) are silk braids.

How about a closer look?

Here’s another suit of armor done in a mix of colors. It’s hard to imagine all those braids being accomplished before the warrior grew old.

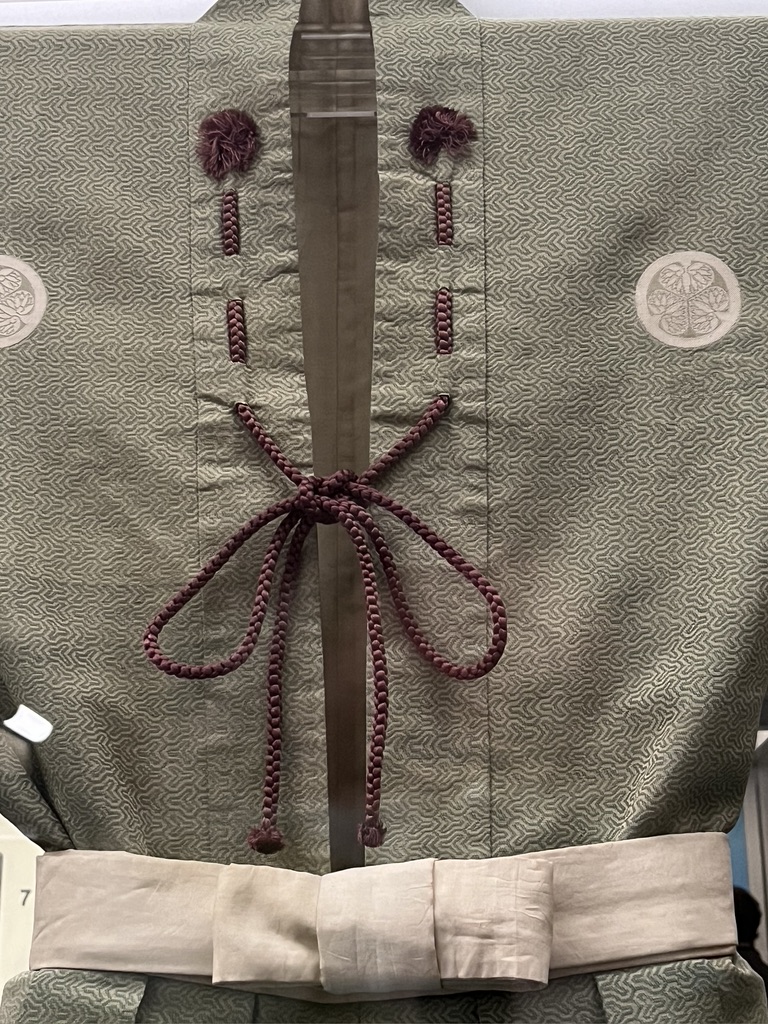

There was this fabric, stunning on its own, embellished with a braid. I love how the tassel at the ends have ‘blossomed’ over time. I’m always overly careful not have the tassels on my braids get disturbed. I think I prefer what has happened here.

Here is another view of this garment showing some hand-painted silk that was braided .

The piece de la resistance in the gallery was this braid on the scabbard of a sword. I have done a similar braid, so seeing this made my day. A touch of the past blending with my small personal history.

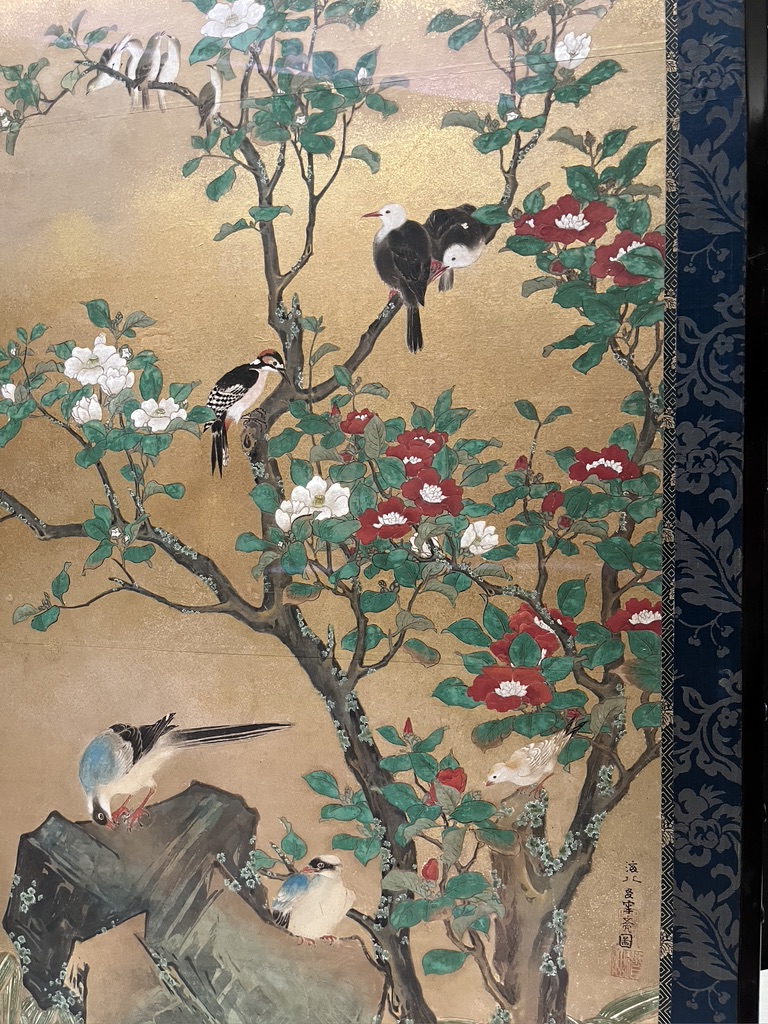

And then there were galleries of scrolls and kimono. I find it fascinating that fabric features so prominently in wall hangings that have painted scenes. This is a culture after my own heart. Look at the edge fabrics that frame this scroll.

We visited Sensoji Temple, the oldest Buddhist temple in Tokyo, and I was thrilled when I saw these women. I felt lucky to get their photo! Sometime later our guide told us that it is quite a popular tourist activity, even for Japanese, to rent kimono to wear while walking about the temple grounds. I’m am still glad I saw this.

It rained quite hard while we were here, but it didn’t dampen our awe at seeing this marvelous place.

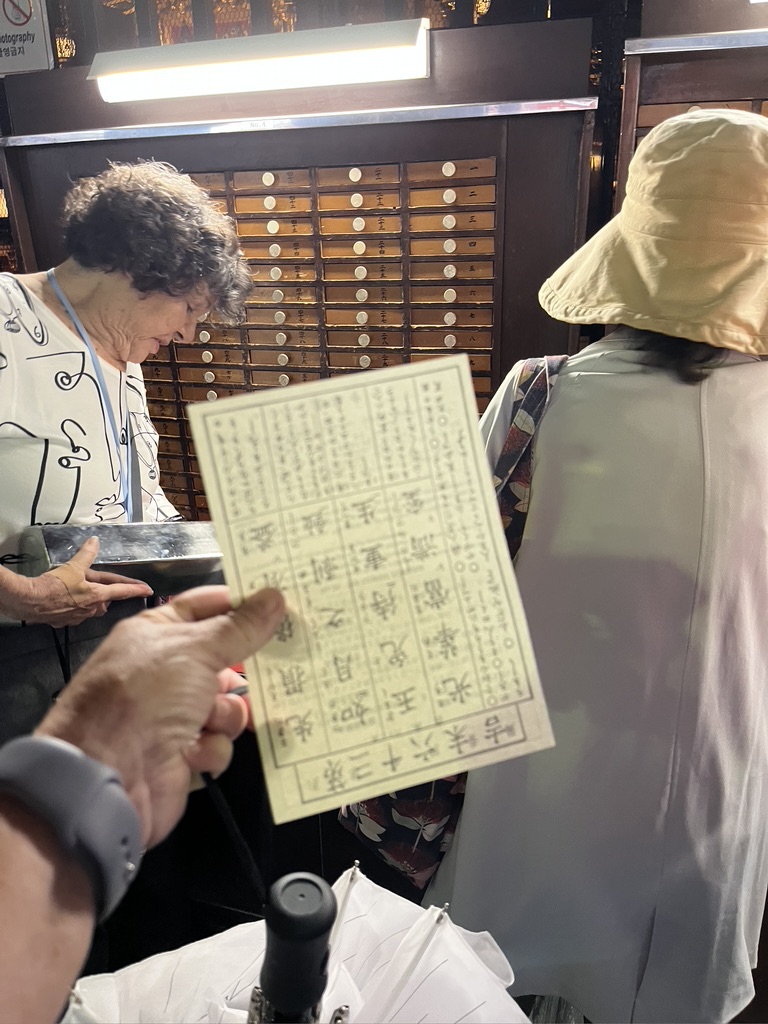

There was an area where you could get your ‘fortune’ for a fee. After you put coins in one end of a large tube, you shook the tube and pulled out a stick from the other end. It had a number on it, and you then pulled a paper out of the drawer with that number. This the paper with my fortune.

My fortune was called “Lowest Bad Luck.” Yikes! When I read it didn’t seem all that terrible. It basically said that my fortune could only go up from here and better times were coming. Well, I was having a great time that day, so if it was going to get even better I felt I was in for some incredible luck! On the other hand, my friend Kari got a card that just said “Bad Luck,” but the description was truly horrible. It was full of doom and hopelessness. She threw it away immediately. I wanted to burn it!

The temple grounds also housed a shopping area. It was such a pretty place, and out of the rain.

I was intrigued with a shop that sold dog and cat treats that looked like people.

After four days in Tokyo we headed north. Our first stop was Kawaguchi to see the Kubota Museum. Have you heard of Itchiku Kubota? I had not, and now I am so glad that I not only know who he is now, but have also seen his work in person, up close. He lived from 1917 to 2003. He was inspired by some dyeing techniques from the 15th c. and he spent his life trying to recreate them and perfect them.

The museum is located where he lived. It includes views of Mt. Fuji, his serene gardens and a wonderful building he designed to house his numerous kimono series. No photos were allowed of his kimono, but we could enjoy the gardens, the tearoom and shop, and take photographs there.

I thought this might be a joke, but it wasn’t! However, none of us saw any primates!

This was my favorite garden of the whole trip.

Can you see the waterfall to the left?

A few us opted to enjoy the tearoom. Our matcha tea came with some confections (on the right) and the tiniest origami crane I have ever seen. I brought that crane home with me!

And the museum was a treasure. I don’t think I’ll ever see kimono as elaborate, intricate, beautifully designed as the numerous series that Kubota made. He had assistants at every stage of executing these designs, but it was he who figured out the techniques and spent decades perfecting the process. The kimono series represent various things. There is a series of views of Mt. Fuji where the famous mountain is shown in every season. There are two series depicting the universe. Breathtaking. Since I could not photograph them, I bought a book, and I will send you to the website.

Here is an image I took from the website. Surely they won’t mind since they don’t allow photography. Isn’t it striking how the summit of Mt. Fuji is in the band at the back of the neck? The kimono in this series are displayed right next to each other, with each kimono sleeve touching the sleeve of the next in the series.

It was hard to leave this museum. I could not comprehend these pieces fully, no matter how long I stayed or how many times I might visit in the future (unlikely). What a rare opportunity to be in the presence of so much technical skill and artistic vision.

The rest of the day we spent at the Fuji Shibazakura Festival. Shibazakura is Japanese for the spring flowers we call ‘creeping phlox.’ It blooms in profusion in this area with views of Mt. Fuji. We stayed for a couple of hours, marveling at the expanse of creeping phlox and also hoping for a view of Mt. Fuji’s summit. The summit was cloaked in moving clouds and we gambled that at any moment the clouds would clear. It was chilly but we were determined to wait for that perfect moment between cloud cover. Our bus driver was on a schedule so our Japanese guide corralled us back into the coach before we got the long awaited view.

The big thrill came when we arrived at our hotel with plenty of daylight left. Our entire group had rooms with balconies that faced Mt. Fuji. Out on the balcony I could see that the clouds were quickly departing. And then there is was!

Kari took my photo to prove I was there, and I took hers! Sadly, my photo is blurry, but I still have to show you! Daryl Lancaster is on the balcony in the background with her camera while her daughter Briana hams it up for my photo. It’s priceless!

The other exciting activity at this hotel was the hot spring baths. Each room came with two kimono for visiting the baths. No bathing suits allowed, but you could bring your tenugui (small cotton towel) that our Japanese guide had given each of us on our first day together. Women entered the bath holding the tenugui in front for modesty, then used the towel the wrap their hair.

Like typical tourists, we took a lot of photos of food, along with photos of our menus in order to attempt to identify some of the delicacies.

It was perfectly acceptable to go to dinner in your kimono, straight from the baths.

Okay, I promise no more food shots, but you must agree, it was an amazing dinner. How many people does it take to plate a 9-course meal for 24 people?

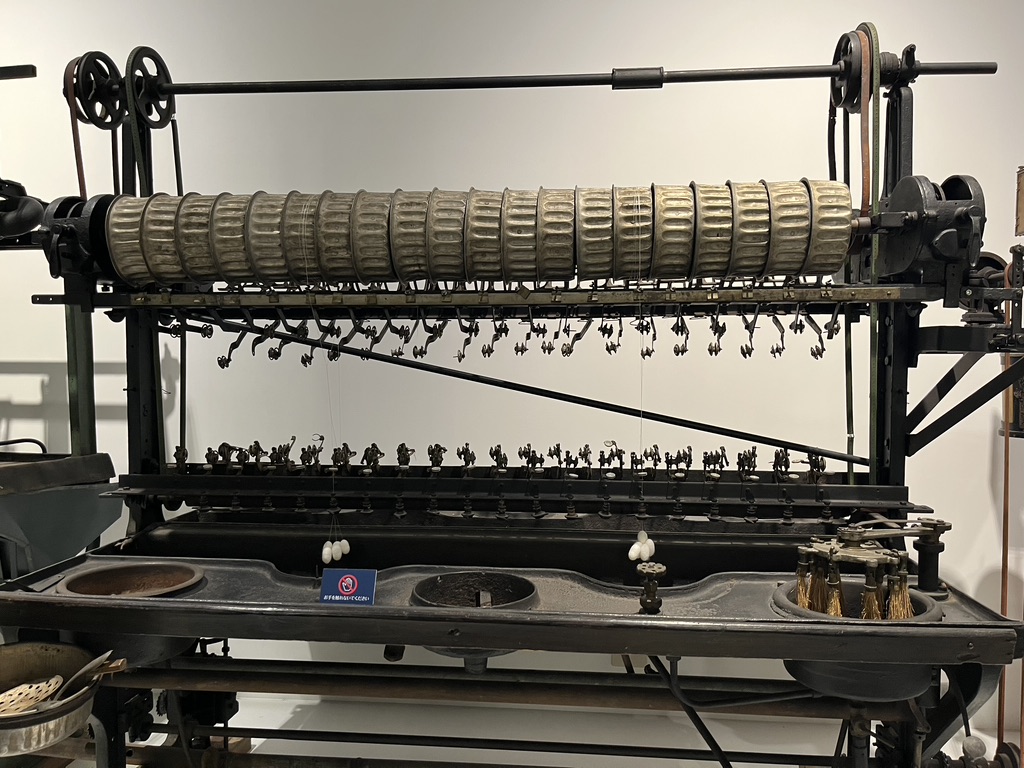

The next morning, off we went for Nagano to visit the Okaya Silk Museum, where there is a collection of reeling machines that span a couple of centuries. Here are some silk worms ready to spin their cocoons.

I don’t feel equipped to describe the changes in the technology of reeling silk, but there is one thing I found quite impressive. No matter how mechanized this process became over the centuries, the use of the little brush that is made from something like a bundle of flax stems, continued to be used. Progress with a bit of low tech material that has remained useful to this process.

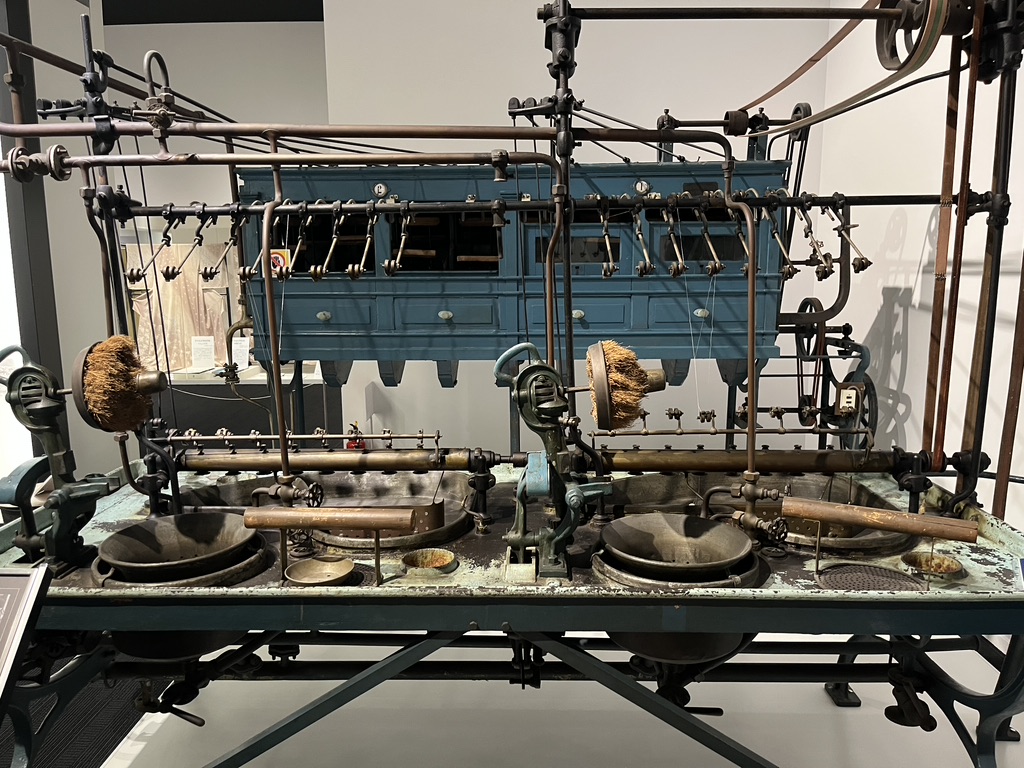

In the earliest times of silk reeling you’d find a woman sitting over a hot pot of cocoons. She’d brush up a filament from a number of cocoons and begin reeling around a form. Sometime later there was this. Notice that brush in front of the sink. That’s the little bundle of plant stalks that remains part of the process to this day.

Then there was this. Note multiple brushes left and center.

Now we have many more reeling stations with a whole battery of brushes on the right.

And voila! Welcome Industrialism!

Some reeled skeins on display in front of the machine used to create them.

There was a shop! There were a number things we all wanted to buy, and high on everyone’s list was this lamp. How to get it home? Hmm…

I bought a silk fan, and some interesting soap. In the process of removing the sericin which is a gummy residue on silk, the sericin can be used to make soap. We all bought several bars of ‘silk’ soap.

On our way to Matsumoto Castle, which retains many of its details from 1592 when it was first begun, we had to walk a few blocks since our bus could not navigate the narrow streets. During that walk I passed this window.

I was so tempted to just walk in to this shop filled with temari balls! But I knew that our Japanese guide spent much of each day counting heads, and disppearing from the group would put her in a tailspin. I asked her if we could visit this shop on our back back from Matsumoto Castle, and it took some convincing. Since she agreed we all had a fabulous experience, and I hope we made the shop owner’s day.

It turns our this area is known for temari balls. This is when I learned that each area of Japan celebrates its traditional crafts by having their man-hole covers decorated to display the local heritage. Interesting!

While heading north each day, we also headed west to the Sea of Japan coast. I had a geographical awakening when I realized how close we now were to both South and North Korea. It was sobering. This is a picturesque area of mountains with terraced rice fields. The views during our ride were so lush with all the spring greens and newly sprouted rice plants flooded with water from the snow melt coming down the mountains. You can read about this area here. Here is a view of rice paddies. We were told that there are no huge, industrial farms as there are in the US. The rice fields nestle into the spaces between residential properties. This is a view in Yamakoshi Village.

We were headed to a kimono factory in Aoyagi. “Factory” seemed a misnomer to me in this place where everything was done by skilled hands. I have about a million photos, and it would take all of them to describe the many dyeing, stitching, stenciling, resist, painting, shibori, and embroidery techniques that happen here. Here are just a few of the techniques happening all through this workplace.

Here is the large dye room. Notice the barrel in a dye vat in the center of the photo. We watched that get opened near the end of our stay.

This man is painstakingly pleating fabric and nailing it to the edge of a barrel. It is like the barrel in the photo above. The fabric inside the barrel will not get dyed, and the fabric on the outside will be dyed with the shibori pleats.

Here one of the dyers is twirling a barrel in a hot dye bath. He constantly flips and twirls the barrel to get an even distribution of dye. Every few minutes he must to go a faucet and fill his rubber gloves with cold water to prevent getting burned.

This barrel is cooling off and will soon be opened.

Opening the barrel, you can see how well the colors were protected inside the barrel.

We were allowed to touch the fabric. Notice the resist design on the edge that was just dyed. Was it stenciled with resist?

The fabric was removed from the barrel and rinsed in cool water.

I’m quite certain this fabric has more processes to go through before it’s ready to become a kimono.

In the showroom were a number of finished kimono. Some of them were the designs we saw in process in the work rooms. A kimono made with this level of handwork costs in the range of $10,000. A one of a kind kimono costs more. Here is fabric similar to what we watched being made.

This was a breathtaking and jaw-dropping experience. I can’t even wrap my head around all the processes that create these kimono.

We visited a small koi farm, and outside, near the koi pools, was this bell. The temptation to ring it was pretty strong. Notice the sign in the lower left of the photo. This briefly gave us pause. What did the bee image mean? Beware of bees? Bee kind? In the long run the need to ring that bell won. Daryl did it, and a flurry of bees emerged. I am not afraid of bees and actually quite like them. They emerged sleepy and not at all aggressive. The bell sounded beautiful–muted and sonorous.

Directly after our visit to Kasuri workshop where we got to weave various ikat dyed wefts (previous post about hands-on workshops), we visited a long established shop that sells salmon products that have been cured in over 100 different ways, called Sennenzake Kikkawa. Most of the items were not meant to be taken out of the country, so there was little for us to buy. The visit included a tasting of locally made sake, and we ejoyed them and bought souvenirs!

Many of the workshops we visited had a display of what the older living space would have been for the family working in the traditional craft we were seeing. Perhaps in some cases, the actual historic living space was preserved. I’m not sure which were original and which were reproductions. This was the historic living space at the salmon shop.

We ended the day with a scenic walk along the shore of the Sea of Japan.

The next few days had workshops that I covered in my previous post. It was a time of rich experiences. I am thrilled that we got to try so many traditional techniques, from weaving with ikat dyed wefts, to weaving with linden tree inner bark, trying rag weaving with hand dyed wefts on modified back strap looms, and dyeing with shibori techniques in indigo vats.

When we left the coast of the Sea of Japan, we took the bullet train from Sendai to Hachinohe. Everyone talks about the bullet trains in Japan, and now I know why. That was the smoothest ride I’ve ever taken! I didn’t know that the trains are connected by magnets. We had two trains connected, and the other train disconnected from ours when it reached the track where it would diverge to a different route. I also didn’t know that what makes the ride so smooth is that the trains rise a little above the tracks due to magnet repulsion. I don’t know enough to say more! We glided at very high speeds!

We were headed to the northernmost area of the main island of Japan, to Hirosaki and Lake Towada. Along some of the drive we followed a stream, and I took a video of the lush surroundings. The video is one minute, and the second half is the best part!

We had a boat ride on Lake Towada which was quite a treat.

We visited Hirosaki Park which rivaled Lake Towada.

One day in Hirosaki we were on our own for lunch, and four of us found a restaurant where there were some handmade dolls right behind my seat. These were soft sculpture dolls, and while I know the Japanese make beautiful dolls, both in porcelain and in cloth, I have no idea what they call them.

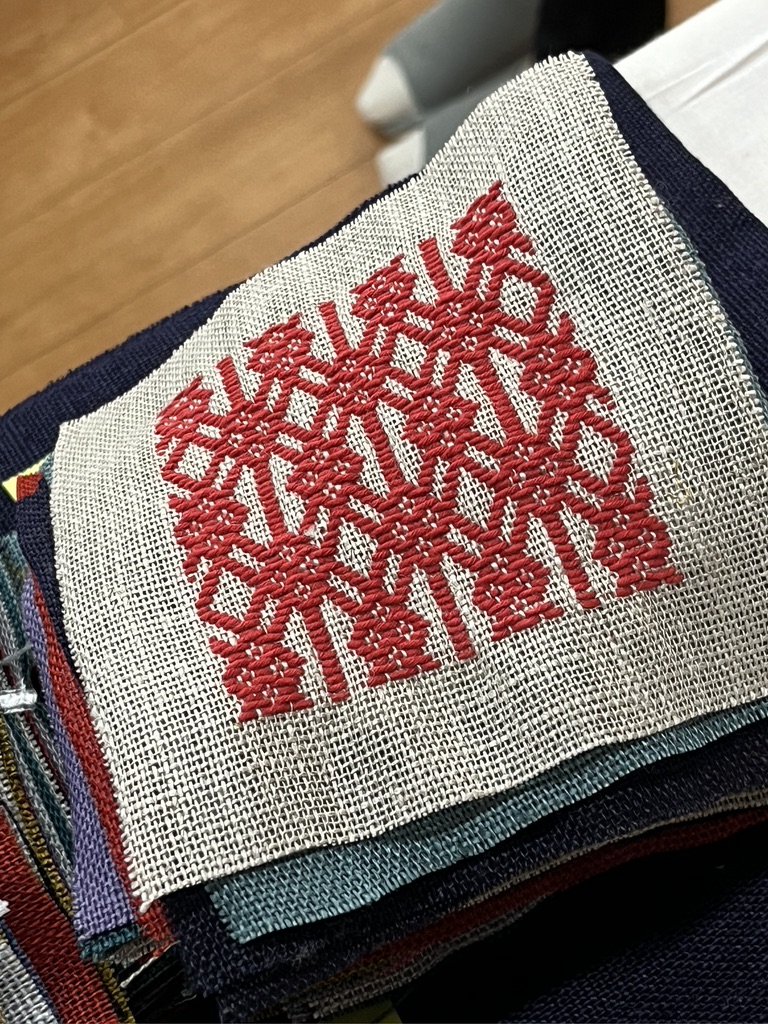

While in this northern area we visited the Hirosaki Kogin Institute. Kogin (hard G) is a type of embroidery that involves straight, long stitches. As I understood the guide, this institute is a cooperative of women who want to keep this tradition going. There was a weaver, but I do not think the dyeing takes place. There were numerous embroiderers as well as women who prepared the embroideries for shipping to various places that had commissioned the pieces.

Here are some of the beautiful designs.

I was particularly enchanted with the little pin/needle holder on this woman’s apron.

Most of the finished pieces were small, to be added in some way to a larger project at the destination where these embroideries were headed. This finished garment was one of the only large items on display. Wow!

This has been a long post, likely the longest post I’ve ever done. Short on words, long on images. We took a longer bullet train from Shin Aomori Station back to Tokyo. Each of us got a lot handwork done during the smooth ride. I made great progress on my second sashiko project.

On our last days in Tokyo as a group, we visited some exciting places for shopping for beautifully handmade items or tools and fabrics to make our own creations. This is the Cohana store which sells tools for hand sewing. I indulged in quite a few lovely treasures.

We visited Toa Textile World and indulged in quite a few purchases there.

We also got to spend some time in a shop dedicated to Japanese fine craft.

And suddenly our time together was coming to an end. We were all a bit exhausted from how much travel we’d done, how many workshops we’d taken, the visual overload of the fine crafts and beautiful countryside we’d seen. But I was not ready to leave. Luckily Kari and I had an additional three days to see and do some things on our own.

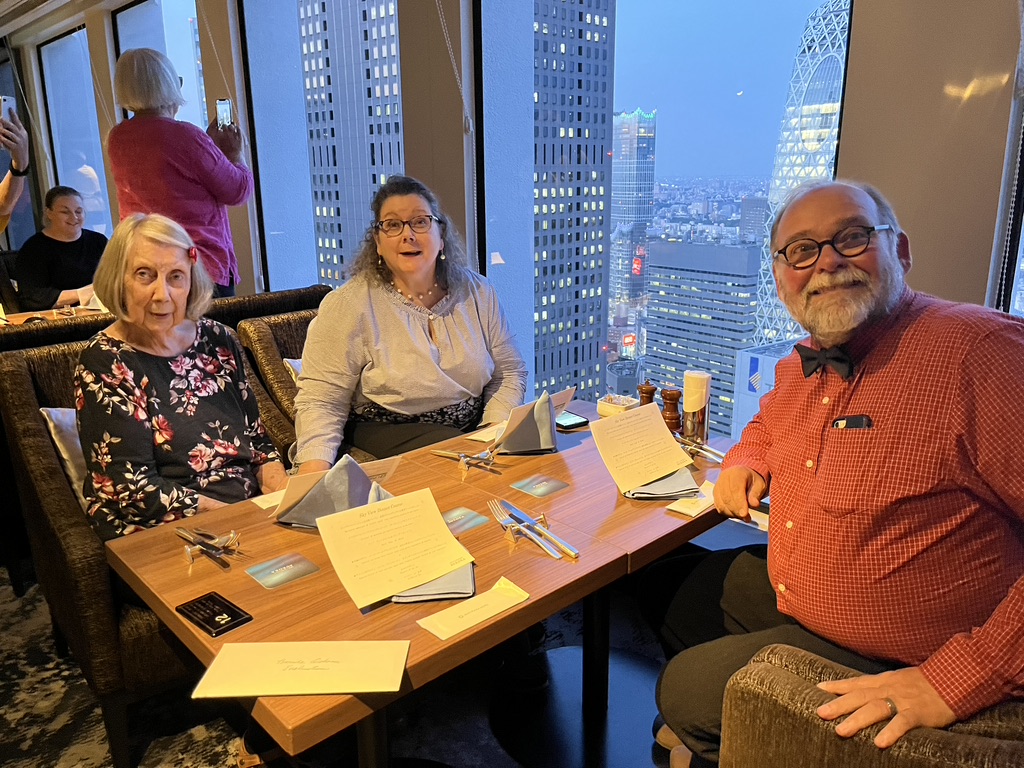

Our final dinner on the 45th floor of Keio Plaza Hotel in Shinjinku Tokyo with impressive views from every table:

If you’ve made it this far I sincerely thank you for letting me share my Japanese journey. With a little luck and a lot of focus I hope to make use of some of the things I learned and experienced on the trip. I know some of my co-travelers have already dressed their looms and are weaving some sakiori projects with rag weft. I need to focus! Bang! Bang!