May is a beautiful time of year in many places, including my home region of New England. This year I chose to step away from home and visit Japan during their glorious mid spring. It was a journey outside of my familiar Western culture into a wondrous world of traditional textiles that are highly valued, into a culture that celebrates its traditions. It was a dazzling time of year to visit Japan!

I can’t imagine how I would tackle a trip like this on my own, so I felt lucky to take a tour led by Sara Bixler of Red Stone Glen. Sara’s well known father, Tom Knisely, joined the tour, and we had an excellent Japanese guide through Opulent Quilt Journeys, who arranged all our destinations and travel. It was the guide’s first time to lead a tour for weavers, and it was her first time to participate in weaving at the workshops she arranged for us. She enjoyed trying her hands at weaving!

Shortly before leaving home I learned that I knew a number of people on the tour, outside of Sara and Tom. My long time weaving friend, Kari, and I were going to travel together and room together on the trip. Then I learned that another old friend, Joan, would be going. What a trill! I haven’t spent time with her since I moved out of New Jersey, more than a decade ago. Also on the trip were Daryl Lancaster and her daughter Briana. While I’ve known Daryl for several decades, I hadn’t seen Briana since she was a small child. Now she’s well into adulthood and a great weaver in her own right. It was a perk to meet Pat White, of MAFA-founding fame, after all these years. We were a great group of 22 weavers who bonded quickly on this trip. There was one husband on the trip, and one daughter who came to accompany her mother.

There was so much to this trip: wonderful opportunities to try both traditional Japanese weaving techniques or materials, and a chance to weave the modern technique called Saori. We saw silk being reeled and processed as well as dyers doing all kinds of techniques, from stenciling and resist applications, to hand painting and shibori techniques. Often all these techniques are combined on one fabric to make a stunning kimono, like this glorious piece.

Since there is so much to cover, I will focus on the workshops we participated in for this post, and I’ll write about the museums, gardens, and temples/shrines in a following post. Everything we did contributed to a once in a lifetime immersion in Japanese textile culture. I’m so glad I made this trip!

Kari and I arrived in Tokyo two days before the tour officially started. We felt we needed that time to acclimate to the time change, a whopping 13 hours ahead of Eastern Daylight Savings time. We arrived at our hotel around 5pm and decided to take a walk to the nearby busy area of Shinjuku Station. It was a step into the iconic culture of busy Tokyo. The station is far larger than Grand Central in NYC, with many shops, fast food joints, and of course, train tracks. As it was approaching dusk the lights of all the computer generated billboards were beginning to glow and the crowds during the evening rush hour were straight out of any images you may have seen of Tokyo crowds. We had never seen so many people in one place ever! They all knew where they were going, so it felt like a choreographed modern dance, with Kari and I being the chink in the cogs. Standing still and taking in the scene, we caused such a ripple in the incredible flow of humanity. Much of the station is underground, like Grand Central, and we were soon lost. We asked a number of times how to get back to the street and got conflicting directions. Finally we asked a woman at a cosmetic counter in a large department store, and she actually left her counter to take us to the nearest stairway to the street level. My big regret from this experience is that I was too awestruck to get any photos of this typical, but nonetheless amazing, view of Tokyo at rush hour. Somehow, I thought to take a couple of photos of the food counters in one department store in the station.

Saori No Mori

The first day of our tour we visited the Imperial Gardens and the National Museum. More on that in the future! The second day of the tour we visited the Saori workshop in Tokyo. This is not the founding Saori workshop, which is in Osaka and still run by the founder’s family, but this Saori location was certainly a large space with lots of looms and yarns. Here is Tom showing his finished piece in front of that wonderful wall of yarn (photo taken by Sara).

At all the workshops we did during the tour, we had to divide into two groups. Here is Group I with their finished pieces. My good friend Kari is in the back row wearing red. Can you find Daryl and Briana?…and Sara?

And here is Group II with their pieces. I’m in the back row, wearing an orange shirt. My good friend Joan is in the front row, 2nd from the left. Pat White is in the front row, on the right.

This was a perfect first workshop. As you know, there are no rules to Saori weaving, just experiment and express yourself. It was a relaxing day. Half of us went to lunch while the other half wove. In the choatic streets of Tokyo we all wondered if we’d find our way back to Saori! No one got lost!

We soon began our trek north to very top of the main island of Japan. Along the way we saw both coasts of the Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Japan. I got a real sense of how close Japan is to both North and South Korea across the Sea of Japan.

Kasuri Weaving Workshop and Ojiya Chimjimi fabric:

This was the day I’d looked forward to since I first got the agenda for our trip. I have a wall hanging in my stairwell that must be close to 30 years old that is from Kasuri Dyeworks. I bought it at a weaving conference those many years ago, and I still love it. To get to visit this place was high on my list.

Ojiya chijimi is a fiber made made from ramie, a bast fiber in the nettle family which is perennial in this region. The process of making a spin-able fiber out of the ramie is very similar to how flax is prepared for spinning into linen. The fibers of ramie are naturally bleached in sunlight on snow covered fields, and this process has been practiced in this part of Japan (the Ojiya region of Niigata Prefecture) for at least four centuries. Older versions of making fiber from different bast plants has existed in this area for a thousand years. Traditionally there was no cotton growing in Japan, and no sheep, so spinning and weaving involved bast fibers and silk.

This display in the museum area of the workshop shows a woman weaving the bast fabric on a traditional loom that features backstrap weaving on a stationary loom. There is a braided cord leading from the curved bar at the back of the loom to the weaver’s foot. The cord has a loop in the end that encircles the weaver’s foot. She changes the shed by pulling her foot back or extending her foot forward. She controls the tension by the backstrap around her hips which is attached to the cloth beam. In the background is a poster of ramie cloth being bleached in a snowy field. (Sorry about the reflection on the glass display!)

Here is an example of weft ikat wound on a reel. The dyes have been carefully placed to create an image when woven. It’s mind boggling to me to imagine trying to do this.

The workshop space where we got to weave a small image in weft ikat is bright with views of the surrounding hills, terraced with early spring rice sprouting in the patties. The space was serene. Outside this workshop area was a display of the centuries of ramie weaving and ikat techniques.

We had several choices of ikat designs to weave, and we could only choose one! It was a hard decision for each of us. The choices were a lady bug, four paw prints, hearts, a swimming koi, and a maneki-necko (the waving cats of good fortune often seen in restaurants).

Some of the looms were set up with complex projects that the weavers on staff were working on. Here is a pattern of butterflies done entirely in weft ikat.

Seeing these weft bundles and the samples they wove made me ask if the weft bundles for our little samples were available for sale. They were! I asked for six sets of the koi pattern, and now I have it. I made a note that the warp was ramie set 10 cm wide on the loom (4 inches) and the warp sett was about 18 epi (71 warp threads in 10 cm width). I’ve now got that info here as well as in my notes. I don’t have ramie for warp, but I have plenty of linen. It will have to do. The photo below shows my woven Maneki-necko and the paper copy template for the six koi weft bundles I purchased.

Each workshop we took got more and more exciting. I cannot imagine a better way of immersing myself in the textiles of any culture than being able to participate as well as learn the history of how and why these techniques were developed.

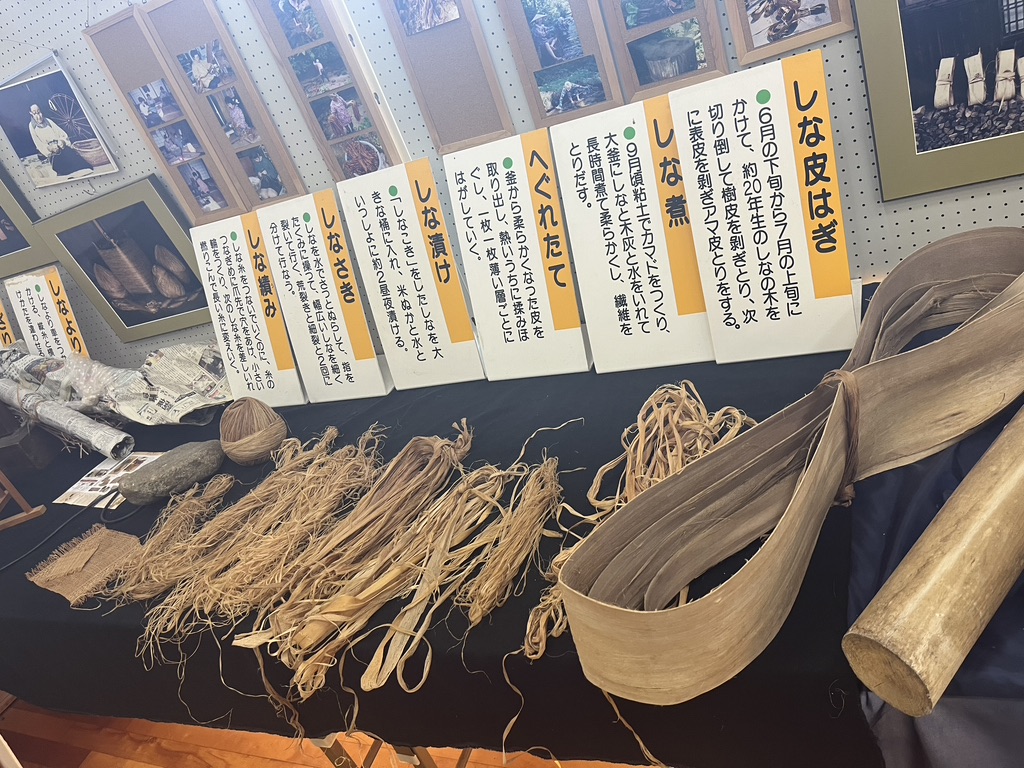

Shinaori

This was my first exposure to this handwoven fabric. It is made entirely from the inner bark of the shina tree, or Japanese linden. Is that the same as the linden trees here in the US? My quick search leads me to say no. There are several types of linden trees. We saw a display on how these fibers are prepared for spinning and weaving. The inner bark is quite a thick section that must first get shaved down, perhaps similar to the way split oak baskets are prepared, but of course, going finer and finer until you have fine fibers like flax or ramie to spin. The sequence of preparation in this photo starts on the right and moves left.

We enjoyed another bright workshop space with views of the neighboring rice fields. It was a perfect day. At the front the room was a display of a traditional living space for those who worked weaving shinaori in the past. This turned out to be a common display in many of the places we visited. The current workshop might be quite modern, but there was often a preserved area that depicted how past generations of weavers would have lived and worked.

I enjoyed this workshop the most of the various techniques we tried. The linden fibers felt wonderful–sturdy and yet pliable. I loved the resulting fabric with its many subtle color changes. Several of us asked if we could purchase this yarn, and we were sad to learn that it was not for sale. It was a joy to weave!

There were items for sale at most of the workshops we attended. I was so smitten with this fabric I wanted to buy many things–most of all the fiber itself.

I treated myself to a hat! I’ll be wearing the most unusual hat of anyone in the Caribbean next winter, as well as here during the New England summer. Lucky me!

I also happened to do a search on Habu Textiles’ site for this fiber, and they have it. I was shocked to learn that it costs a dollar per yard. Hmmm… I think the prices of the finished goods in the shop were quite reasonable. I couldn’t afford to weave any of them myself at $1/yd. I’m so glad I indulged, and I love my woven sample.

Again, we had to weave in two separate groups. While one group was weaving the other group shopped and walked around the village, which seemed quite remote. I have since learned that there are only a handful of villages that continue this tradition of weaving with this fiber. There was interesting information here. Our workshop was in Sekigawa, one of only four remote mountain villages that continue this tradition. Outside the workshop some of us found a small shrine in the village. It was a memorable experience to be in such a remote area of Japan.

The next day we took the bullet train from Sendai to Hachinohe, where we visited Lake Towada and Hirosaki, at the northernmost area of the main island of Japan.

Nanbu Sakiori no Sato

Sakiori is a form of rag weaving, and this Japanese tradition shows the height of what can be done with rags as weft.

The looms here were also partly backstrap in nature. There were two shafts on these looms, and the curved beam at the back of the loom controlled the movement of those shafts through the use of the braided cord that leads from the curved beam to a loop the weaver puts around her foot. As you can see, it is a large studio. Still, we broke into two groups for weaving. This was probably due to the number of staff available to guide us.

Here you can see a woman working on her own project. You can see the braided cord that goes around her foot, and you can see the backstrap she is wearing. The warp is striped and the woven fabric has subtle coloration due to the printed fabric strips used for weft.

Every loom had different warp on it, so it was fun to see what each of us got as an end result. We also had baskets full of fabric strips to choose from. There was a man who seemed to be in charge of the whole operation. He stood next to the woman who was traveling with her mother and was not a weaver herself. There was a bit of a learning curve to using these backstrap looms, so it was a hurdle for the daughter. I happened to be sitting next to her as the enthusiastic man would yell to her, “Tension!! Bang! Bang!” He sounded quite aggressive or maybe even angry as he yelled at her, but I’m certain he was trying to encourage her. It was frightful and funny at the same time. Many of us will remember this for a long time.

“Tension! Bang! Bang!“

I was so busy weaving I did not get enough photos! –and how I regret not getting a photo of Bang, Bang! man. This photo was taken with Sara’s phone, of the whole group at the end of our Sakiori weaving session.

Shibori Indigo Dyeing:

Our last participatory workshop took place in Hirosaki at the top of the mainland island. Here is the workshop entrance from the busy street in the center of town.

This place is well known and popular. The whole time we were there, whether shopping or dyeing, the shop was full of Japanese customers.

There was a display of the items used in making the dye and using the dye. Here is one of the large dye vats not in use. To the left of the dye vat are some dried indigo leaves. It is in the showroom.

Also in the showroom is a large mortar and pestle that was used to grind the indigo cakes.

This is where the fun takes place. We were each given an apron to wear and waterproof gloves. The workers were wearing such creative aprons. This makes me think about what I’d like to do with my indigo vat at home. Indigo dyed aprons might end up as part of future gift giving.

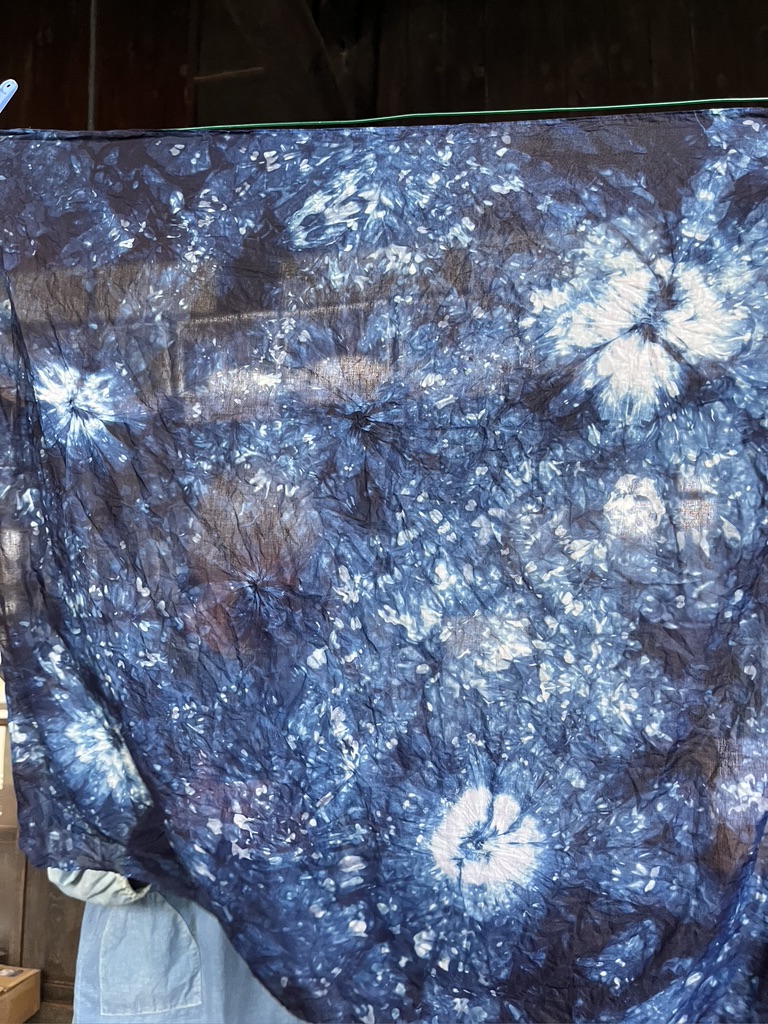

We had a few options on how we wanted to dye our scarves. I chose the technique I’ve always called sand dollars, but these dyers called it fireworks. In the past I’ve always used a chopstick or bamboo skewer to make a point in the fabric and then wrap a piece of seine twine around the skewer a number times. I then remove the skewer and use it to make another sand dollar in a different area of the fabric. In this technique we simply took our wet fabric and twisted a section with our fingers. It held in place as we did another section until we had as many twisted areas as we wanted. Then we ‘scrunched’ the whole fabric together and placed it in a wire cage. Three of us did this together and shared the wire cage.

Each vat had a heavy wooden cover which was removed. The indigo was at room temperature.

While we held our pieces in the vat we tried not to move which would introduce oxygen into the vat. The cages were dipped three times, for 2 minutes each dip.

Once out of the vat, we watched the magic of our pieces turning bluer and bluer as we waved them in the air.

Then came the rinsing party at a clever set up with multiple sinks and drainage.

The lightweight cotton fabric dried quickly on a line in the studio. We shopped while our scarves dried. I bought a scarf and an indigo dyed skein of traditional cotton used in sashiko embroidery.

The traditional noren (curtain) at the entrance to the building.

Each of these experiences is a treasure to me. The ability to weave some small item that is a part of Japanese history, and the ability to learn the origin and uses of these traditional works, has been far beyond what I ever expected. Most of my learning has come from books or from taking a class with someone else who has learned from a primary source.

One cultural tradition from this trip that I hold dear is the act of bowing, and the way all the workers we visited came outside to bow and wave goodbye to us as we left their presence. It even happened at large hotels. The staff would come stand beside our bus and bow and wave to us as we headed off into our future. Eventually these thoughtful goodbyes brought tears to my eyes. Wouldn’t life be sweeter if we all bowed to each other in salute? This particular incident happened at the Sakiori workshop. I remember these weavers with affection, along with everyone who crossed my path on this journey.

Now that I’ve been exposed to an entirely different culture and learned a few things from primary sources, I don’t want to stop. There are so many places to see, so many techniques to learn from all over the world. In my next post I’ll focus on images of the country and the museums and shrines we visited.

3 responses to “May in Japan”